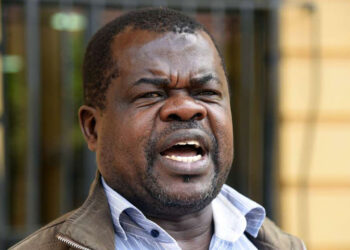

A groundbreaking traditional medicine regulation bill was introduced in Parliament this week, aiming to regulate, research, and commercialize traditional and alternative medicine practices across the country. Tabled by Seme MP James Nyikal, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Bill, 2025, seeks to integrate herbal remedies into the national healthcare system while imposing strict penalties for false claims, including up to three years in prison or fines of Sh3 million (approximately $23,000).

The legislation addresses the widespread use of traditional medicine, particularly in rural areas, while tackling issues of safety, efficacy, and biopiracy.

The bill establishes a robust framework for KEMRI to oversee the validation of traditional remedies through biochemical and clinical trials, ensuring they meet national and international safety standards. With an estimated 80% of the population relying on herbal medicine for primary healthcare, especially for non-communicable diseases like diabetes and hypertension, the legislation aims to bridge the gap between traditional practices and modern healthcare.

It mandates the creation of a national database to document validated traditional knowledge, protecting it from exploitation and ensuring communities benefit from commercialization.

The bill also prohibits adding unauthorized substances to medicines, selling ineffective products, or making unverified claims about herbal treatments.

False claims about traditional remedies, such as exaggerated cures for cancer or infertility, will face severe penalties under the proposed law. Offenders could be fined up to Sh3 million or imprisoned for three years, addressing concerns about quackery that have undermined trust in herbal medicine.

A 2021 study by the University of Nairobi found that 64% of cancer patients at Kenyatta National Hospital used herbal remedies, with 55% reporting disappointment due to unverified claims, highlighting the need for regulation.

The bill also criminalizes manufacturing or selling products in unhygienic conditions, aiming to protect consumers from contaminated or unsafe remedies.

KEMRI’s expanded role includes managing biobanks and intellectual property to prevent biopiracy, where foreign entities exploit local medicinal plants without compensating communities.

The bill aligns with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines promoting integrative healthcare, drawing inspiration from nations like China and India, where traditional medicine is formalized.

A Scientific and Ethics Review Unit will enforce ethical standards, while training programs will build capacity among herbal practitioners and healthcare professionals.

This move addresses long-standing concerns about the lack of oversight, as noted in a 2017 Pan African Medical Journal review, which criticized ambiguous regulations allowing unqualified practitioners to thrive.

The legislation builds on earlier efforts, such as the lapsed Health Laws Amendment Bill, 2021, which sought to regulate herbalists but faced delays due to definitional challenges around “community” ownership of traditional knowledge.

The 2017 Health Act directed the Ministry of Health to develop referral guidelines between traditional and conventional practitioners, but progress stalled, leaving a regulatory void exploited by unscrupulous vendors.

The new bill responds to calls from groups like the Integrated Medicine Society of Kenya (IMSK), which in 2024 urged for policies to ensure quality and safety in traditional medicine, citing restrictive laws like the 1925 Witchcraft Act that once labeled herbalists as “witchdoctors.”

Social media reactions on Twitter reflect mixed sentiments. Supporters, including herbalists like James Njoroge of Almed Health Products, praise the bill for legitimizing their practice, while skeptics worry about overregulation stifling small-scale practitioners.

A 2020 ScienceDirect study noted that plummeting plant resources and low acceptance of traditional medicine due to past demonization pose challenges, which the bill’s conservation measures aim to address through nurseries and herb gardens.

Critics, however, argue that the high cost of clinical trials could exclude rural herbalists, echoing concerns raised by Dr. Maina Mwea in 2012 about financial barriers.

The bill’s passage could position Kenya as a leader in African integrative healthcare, supporting sustainable harvesting and protecting medicinal biodiversity.

By empowering KEMRI to regulate labeling, advertising, and market surveillance, the legislation aims to restore public trust in herbal remedies while fostering innovation. As Parliament debates the bill, its success will depend on balancing scientific rigor with cultural sensitivity to preserve a practice deeply rooted in the nation’s heritage.