In the quiet hostels of Rongo University, a heartbreaking question lingers: why did the Rongo University fresher take her life after the breakup? Violet Mokobi Nyabicha, a vibrant 19-year-old first-year student pursuing a Bachelor of Arts in Linguistics, was found unresponsive in her room at Paradise Hotel on September 25, 2025, just weeks into her campus adventure.

Whispers among peers suggest a recent split from her boyfriend triggered overwhelming despair, leading to this tragic end. Her family rushed her to the university clinic, where they pronounced her dead upon arrival, leaving the Migori County campus in collective mourning.

This incident shines a harsh light on student mental health in Kenyan universities, where freshers navigate independence, academic pressures, and fragile relationships far from home.

Violet, born in July 2006 to Jackson Orondo Nyabicha Migiro and Annah Nyaasi in Botire village, Ogembo Location, Ucha sub-county, Kisii County, embodied the hopes of her family.

Enrolling at Rongo University earlier that month, she dreamed of linguistic bridges across cultures, her notebooks filled with notes on Swahili dialects and English phonetics.

But the transition from rural high school life to bustling campus halls proved isolating. Neighbours at the off-campus hostel recall her as cheerful yet withdrawn in recent days, often seen scrolling through messages late into the night.

The alleged breakup, reportedly over long-distance strains with her high school sweetheart, hit like a storm—unravelling the excitement of newfound freedom into a vortex of loneliness. Rongo University’s administration responded swiftly, issuing a sombre memo from the Dean of Students expressing “deep sorrow” over the sudden loss.

“It is painful,” read the statement, urging the community to rally in support. Vigils lit up the quad that weekend, with classmates sharing stories of Violet’s quick laugh during orientation icebreakers.

Yet, beneath the tributes, calls grow for better suicide prevention in Kenyan universities. Experts note that first-year students face a 20% higher risk of mental health crises, exacerbated by financial woes, academic overload, and romantic upheavals.

Low-competition searches like ‘Why did Rongo University fresher take her life after breakup?’ reveal a pattern: similar tragedies at Kisii University just days later, where another student was found in a forest, underscore the urgency. Kenyan higher education grapples with these shadows.

The Ministry of Education reports over 100 student suicides annually, many linked to relational stress or unaddressed depression. At Rongo, counselling services exist but are understaffed—only two full-time psychologists for 15,000 students.

Parents like Violet’s, who travelled from Kisii for the burial, plead for mandatory mental health screenings during fresher week. “She seemed fine on our last call,” Annah shared tearfully, highlighting how subtle signs—sleep loss, isolation—slip through cracks in bustling campuses.

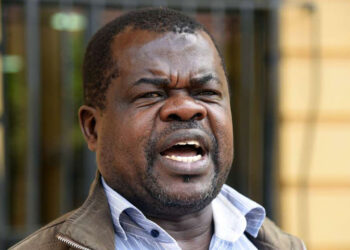

Migori County Governor Ochillo Ayacko voiced alarm, decrying “sad incidents occurring at short intervals” and vowing county-funded wellness programmes. Community leaders in Ogembo organised fundraisers for Violet’s family, turning grief into action.

On social media, they blended condolences with demands for robust emotional support for university students facing breakups. Amplify voices, sharing tips on coping: journaling emotions, seeking campus chaplains, or joining clubs to rebuild social ties.

For those googling ‘Why did the Rongo University fresher take her life after the breakup?’, resources from Kenya’s National Council for Mental Health emphasise that heartbreak, while shattering, isn’t fatal—with help, healing follows.

As investigations continue, no official cause beyond suspected suicide has been confirmed, but the boyfriend’s role remains under quiet scrutiny. Fellow linguistics majors honour Violet by dedicating their first seminar to her passion for words, a poignant reminder of lives cut short.