Kenya’s GMO cassava commercialisation takes a giant leap forward today, as the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) opens the floodgates for public input on rolling out disease-busting genetically modified cassava across 18 key farming heartlands, marking the East African powerhouse’s boldest bet yet on biotech to feed its growing masses.

This isn’t just lab talk anymore; it’s boots-on-the-ground reality for smallholder farmers battered by crop-killing plagues, with the Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) leading the charge to turn trial fields into thriving harvests that could slash losses and supercharge rural economies.

The move, detailed in a fresh Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report up for 21-day scrutiny, spotlights cassava – Kenya’s unsung starch staple, a lifeline for over 1.5 million households churning out porridge, ugali, and export chips.

Picture this: vast swathes of coastal and western farmlands, from the sun-baked dunes of Lamu to the misty hills of Homa Bay, soon dotted with resilient roots engineered to shrug off cassava mosaic disease (CMD) and the sneaky cassava brown streak disease (CBSD).

These twin terrors have gnawed away up to 70% of yields in bad years, leaving families scraping by on wilted dreams. “We’ve waited too long; this GMO cassava is our drought in the dark,” shared Mama Achieng, a veteran grower from Kisumu’s lakeside plots, her calloused hands gesturing toward parched test patches where KALRO’s hybrids have already pumped out 40 tonnes per hectare – double the national average.

KALRO’s blueprint, greenlit by the National Biosafety Authority (NBA) back in June 2021 for environmental release, targets a hit list of 18 counties primed for the push: Lamu, Kilifi, Kwale, Taita Taveta, Makueni, Kitui, Machakos, Tharaka Nithi, Embu, Nakuru, Baringo, Kakamega, Bungoma, Busia, Vihiga, Kisumu, Migori, and Homa Bay.

It’s a strategic sweep through arid ASALs and fertile basins where cassava is king, backed by partnerships with county governments for seed banks, farmer clinics, and climate-savvy training.

KEPHIS inspectors will hawk the biosafety reins, ensuring no rogue roots wander off-script. The payoff? A projected KSh 60.7 billion windfall over three decades, per a new KALRO-backed study, flipping the script on the KSh 20.3 billion bleed from biotech foot-dragging on crops like Bt cotton and maize.

But it’s not all smooth sailing on this green revolution express. Whispers of worry ripple through village barazas: will these lab-born tubers taint our traditional tastes? Spark superweeds?

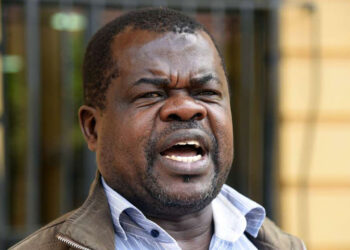

The EIA flags risks like illegal seed swaps and spotty storage, pledging fixes from hermetic bags to community watchdogs. Enter the misinformation minefield – that sneaky saboteur Daniel Kyallo, KALRO’s agribusiness czar, calls “the real pest”.

“The issue is misinformation, not regulation,” Kyallo told reporters, his brow furrowed over data decks showing Nigeria and South Africa lapping Kenya in GMO gains.

“It’s clouded public understanding, keeping us behind while farmers foot the bill in lost harvests.” Anti-GMO holdouts, echoing 2023 court skirmishes that stalled other releases, are already firing up petitions, but proponents point to rigorous NBA nods and global nods from the WHO on safety.

As Kenya’s plate tectonics shift under climate heat and a ballooning 55-million-strong populace, this cassava coup could rewrite food security scripts. From Kilifi’s fishing hamlets to Migori’s maize belts, it’s a shot at self-reliance – less imported wheat, more homegrown resilience.

“This isn’t playing God; it’s giving farmers wings.” With public comments closing mid-November, the clock ticks on a verdict that could seed prosperity or sow doubt. In the end, as NEMA’s doors swing wide, one truth roots deep: Innovation’s the fertiliser; acceptance, the rain.