In a landmark shift for Kenya’s wildlife heritage, the Amboseli National Park handover to Kajiado County was sealed on October 26, 2025, transferring daily stewardship from national to local hands after 52 years under central control.

The ceremony, held amid the park’s iconic elephant herds and snow-capped Kilimanjaro vistas, marked a devolution win for Maasai communities long advocating for a say in their backyard’s bounty.

Kajiado leaders hailed it as “reclaiming our roots”, with the county now helming tourism ops, conservation drives, and ranger patrols – while the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) retains ultimate ownership and regulatory reins.

This change heralds a new era for the 392-square-kilometre treasure, renowned for its red-dust trails and Big Five sightings that attract 500,000 visitors annually.

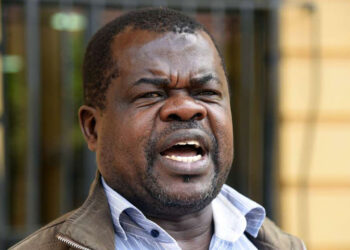

The handover unfolded at Kimana Gate under a canopy of fever trees, with Governor Alfred Koitany clasping a symbolic key from KWS Director Erastus Kanga amid ululations from olmarei (Maasai elders) in full regalia.

“For decades, we’ve watched our savannahs thrive from afar; now, we’ll nurture them up close,” Koitany boomed, his beaded necklaces glinting in the equatorial sun.

Kanga, ever the pragmatist, shows the hybrid model: “KWS stays the guardian; Kajiado brings the heartbeat. It’s synergy, not surrender.”

Signed amid a backdrop of acacia silhouettes, the agreement stems from the 2010 Constitution’s devolution push, accelerated by 2023 audits revealing national mismanagement, like poaching spikes and underfunded anti-snaring ops that culled 200 elephants in 2024 alone.

Amboseli’s devolution isn’t just paperwork; it’s a lifeline for Kajiado’s 1.2 million souls, where herding clashes with tourism dollars.

The county’s new remit includes gate fees, raking in Sh1.2 billion annually, and eco-lodges like Tortilis Camp, whose revenues will now funnel into community saccos for beekeeping and boma schools.

“Tourists snap our elephants, but locals get the scraps; that flips today,” grinned Jane Lesinko, a 32-year-old ranger trainee from Olgulului village, her uniform crisp against the thornbush.

Conservationists at the Amboseli Trust for Elephants, who’ve tracked the park’s 1,700 jumbos since 1973, see upsides: Localised patrols could slash human-wildlife skirmishes by 30%, per their models, blending indigenous lore, like Maasai fire dances to deter crop raiders, with drone surveillance.

Sceptics murmur about teething troubles. National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) watchdogs flag risks: Will Kajiado’s lean budget, Sh4.5 billion for 2025, stretch to anti-poaching choppers or climate-resilient water pans amid droughts that shrank the park’s swamps by 40% last El Niño?

“Oversight’s key; one slip, and Amboseli’s magic fades,” warned ecologist Dr Musyoki Mbuvi in a pre-handover op-ed. Koitany countered with a Sh500 million masterplan, eyeing carbon credit deals with Norwegian funders to bankroll solar fences and youth eco-guides.