The government has set aside Sh100 million to design a Kenyan national dress after a previous Sh50 million attempt failed.

The Kenyan national dress is traditional attire symbolising Kenya’s cultural identity and diversity, according to PS Ummi Bashir.

Only after its launch in 2004, Kenya’s KSh50 million national dress became a white elephant project. It was revived in 2008 with another Ksh 50 million. However, to date, the national dress project has yielded no tangible results.

Kenyans’ stubborn adherence to their Western attire raised fears at that time; eventually, the national dress project in Kenya failed.

Unlike 2008, this time PS Ummi Bashir says commentators and designers cautioned against hastily rushing into presenting a national garb to Kenyans.

One of the individuals who voiced concerns about the project’s implementation haste was the previous designer, Lucy Rao of Rialto Fashions.

First launched on September 14, 2004, the national garb project eventually became a white elephant. It was revisted in 2008.

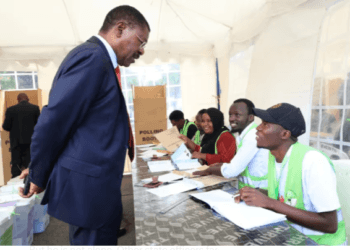

This was especially evident on Kenyatta Day, October 20, 2008, when dignitaries arrived for the national celebrations at Nyayo National Stadium in their Western and various African attire, but no Kenyan national dress.

In June 2004, the designer stated that the public—not designers—should take the lead in determining the direction of the national dress four years down the line.

An agricultural engineer who stumbled into fashion design as a hobby but turned it into a vocation, Rao, said locally designed clothes could not beat their second-hand counterparts from the West that sell for a song in Kenya, where almost half of the 34 million population live on less than Sh80 (US$1) a day.

Rao identified several factors contributing to this non-competitiveness, including the high cost of production, labour, rent, and the scarcity of readily available fabrics in Kenya.

Coupled with low purchasing power, the award-winning plough champion Rao said this area needed to be addressed for people to afford locally-made clothes like the national dress.

“Despite the necessity of the national dress for identity, I am concerned about its haste,” she expressed.

“No national dress should be uniform; it should come from the people.”

“Designers and the government can only follow the public trend and not attempt to impose anything on the people.”

Rao’s sentiments proved to be true when Rialto Fashions held a fashion show in Rome in December 2004.

She had expressed fear that the rush was aimed not at benefiting the Kenyan masses but at certain individuals from the hefty Sh50 million (about US$625,000 or 515,000 euros) national dress budget.

During the opening of an exhibition on mountains at the Goethe-Institut in Nairobi on September 15, 2004, Prof. Wangari Muta Maathai jokingly remarked that the reason she wasn’t wearing a national dress was because she had washed hers, and she only had one pair given to her by the national design team.

Indeed, the only time former Vice President Moody Awori, then Roads Minister Raila Odinga, Industry Minister Dr. Mukhisa Kituyi, Culture Minister Ochillo Ayacko, National Heritage Minister Najib Balala, and Environment Assistant Minister Prof. Maathai put on the ‘national dress’ was on its launch a day before the Nobel Laureate Prof. Maathai opened the Facing Mountains exhibition.

The Unilever-sponsored search for Kenya’s national dress began in April 2004 during Balala’s tenure as Culture Minister.

A nationwide vote via short message service (SMS) and road shows was said to have been used in the selection of the national dress: a cloak over a kitenge-like outfit for men and a flowing dress for women.

The cloak features the red, black, green, and white colors of the Kenyan flag, along with beads that are believed to be essential to most Kenyan cultures.

The search for the national dress in 2004 took seven months at a Sh50 million budget that, critics contend, could have been channelled to other areas of pressing needs like public healthcare, education, and food production.

Although Ayacko was hopeful that Kenyans would now don their national dress—which has no name yet—instead of the Western suit, Ghanaian Kente, or Nigerian Agbada, his dream is like a mirage that fades with passing time.

Declaring their creation public property “to be used by any Kenyan, at any time and anywhere,” the National Dress Team appealed to local designers, tailors, and other clothing manufacturers to adopt the concept and “make it in colors, sizes, or materials that they prefer to use.”

The designer added that locally designed clothes could not beat their second-hand counterparts from the West that sell for a song in Kenya, where almost half of the 34 million population live on less than Sh80 (US$1) a day.

Some of the reasons Rao had advanced for this non-competitiveness were that unlike mitumba or Marehemu George clothes that come cheaply by ship, locally designed clothes are more expensive due to the high cost of production, labour, rent, and non-readily available fabrics in Kenya.

Coupled with low purchasing power, the award-winning plough champion Rao said this area needed to be addressed for people to afford locally made clothes like the national dress.

VP Awori expressed hope that the national dress would not only help promote Kenya’s diverse cultures, but also give life to the doomed textile industry.

The National Dress Team had unveiled six concepts based on sash, cape, apron, and cloak for public scrutiny during the Kenya Fashion Week in July 2004.

Kenyans reportedly chose the cloak concept over the apron concept, despite the appearance of musicians, emcees, and beauty pageant contestants in the run-up to the national dress selection.

However, why they are reluctant to do what they chose—if indeed they voted—is difficult to explain.