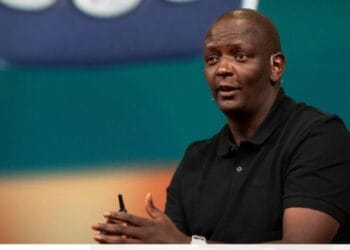

Ruto’s Singapore slum force relocation tactic draws sharp reactions as President William Ruto invokes a tough-love blueprint from the Asian powerhouse to tackle Kenya’s urban sprawl, hinting at bold moves to uproot millions from shantytowns into towering apartments.

Speaking at a housing summit in Nairobi on November 5, Ruto recounted a chat with Singapore’s president, revealing how the city-state strong-armed residents from squalid camps into high-rises on the 10th and 15th floors decades ago.

“They used force to make people move from the slums into houses on the 10th and 15th floors,” Ruto shared, his tone a mix of admiration and resolve, before pivoting to a fresh example closer to home: Tanzania’s National Social Security Fund (NSSF) is breaking ground on twin 22-storey behemoths in Upper Hill, Nairobi, set to redefine the skyline and house diplomatic hubs.

The remarks, delivered amid a push for Kenya’s Affordable Housing Programme, landed like a thunderclap in a room packed with developers, activists, and policymakers.

Ruto painted Singapore’s 1960s purge of kampungs, or villages, as a masterstroke that birthed a gleaming metropolis from muddy chaos.

Back then, under Lee Kuan Yew’s iron grip, bulldozers rolled in, evicting holdouts to public Housing and Development Board flats, where 90 percent of citizens now own homes.

“What was once a sprawling slum has been transformed into a modern housing estate with decent living conditions,” Ruto echoed, nodding to the island’s leap from post-colonial poverty to global envy.

Critics, though, bristled at the force angle. “Singapore’s success came with consent and compensation, not coercion. Kenya’s not a dictatorship,” fired back human rights lawyer Maina Kiai on social media, questioning if Ruto eyes similar sweeps for Kibera’s 250,000 souls or Mathare’s labyrinths.

Ruto wasted no time linking the anecdote to action, spotlighting the Tanzanian towers as proof East Africa can build big and borrow boldly.

“Today, Tanzania’s Social Security Fund is constructing one of the tallest buildings in Upper Hill, Nairobi,” Ruto beamed, framing it as a neighbourhood flex that could inspire Kenya’s own vertical villages.

Engineers project completion by 2027, with solar panels and green roofs nodding to sustainable swagger, but locals grumble over traffic snarls from the site’s hulking cranes already choking the CBD commute.

This isn’t Ruto’s first nod to Singapore’s script. In September, he vowed to erase slum life for seven million Kenyans, touting 90 per cent homeownership rates across the strait as the gold standard.

His administration’s Boma Yangu portal has notched 700,000 registrations for subsidised units, but delivery lags at under 10,000 amid land wrangles and funding droughts.

Enter the force factor, activists fear it greenlights evictions without fair play, recalling the 2023 Mukuru demolitions that left 20,000 homeless overnight.

“We’re not against progress, but progress shouldn’t bulldoze the poor,” urged an Amnesty Kenya official in a statement, urging Ruto to embed community buy-in like Singapore’s phased resettlements, where resisters got court nods only after failed talks.

Ruto’s boosters see genius in the grit. “Singapore didn’t ask permission to prosper; they planned and pushed. Kenya needs that spine to house the hustlers,” tweeted UDA senator Aaron Cheruiyot.

The Tanzania tie-in adds regional spice, underscoring EAC bonds as pension funds chase yields abroad. NSSF’s boss, Emmanuel Tutuba, hailed the towers as a “diplomatic dividend”, projecting Sh2 billion in annual rents to pad Tanzanian retiree cheques.

For Nairobi, it means jobs for 500 locals during construction and a prestige boost to a skyline rivalling Lagos or Addis.

As the sun dipped over the city on November 5, Ruto’s words hung heavy, a clarion for change or a chill wind for the vulnerable. Will Kenya’s slums yield to skyward summons or spark street-level standoffs?