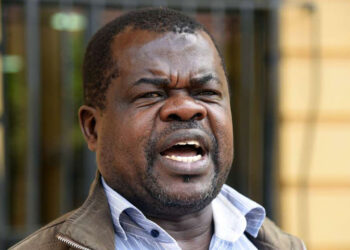

In a surprising turn in the Chacha Mwita crypto terror probe, the prominent Kenyan High Court lawyer addressed the nation for the first time since his release from custody on a Sh5 million bond. Mwita, who faced grave accusations of channelling cryptocurrency funds from a blacklisted terrorist entity, firmly rejected the claims during an exclusive interview aired on social media platforms late Tuesday.

Authorities had alleged that the transactions, totalling modest amounts like Sh42,000 via M-Pesa and Binance wallets, supported recruitment efforts for the Islamic State East Africa cell. This development has sparked widespread debate on the balance between national security and the rights of legal professionals in Kenya.

Andrew Chacha Mwita, a Mombasa-based advocate renowned for defending clients in high-stakes security cases, was arrested on November 14, 2025, in a sweeping Anti-Terrorism Police Unit operation across multiple counties. The sting targeted suspected financiers, recruiters, and supporters of extremist networks operating in Nairobi, Mombasa, Kapseret, Moyale, and Marsabit.

Detectives from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations painted a picture of a shadowy web involving digital currencies to evade traditional banking scrutiny. According to court documents, Mwita allegedly facilitated transfers from accounts tied to the Islamic State, with prosecutors estimating the funds could bolster operations far beyond Kenya’s borders.

The heart of the case revolves around cryptocurrency’s role in modern terrorism financing in Kenya. Experts note that platforms like Binance have become hotspots for illicit flows due to their anonymity and speed. In Mwita’s instance, investigators claimed he used several mobile numbers to receive payments, some converted from Bitcoin, purportedly to aid in radicalising and mobilising youth.

Sources close to the probe revealed concerns that these resources might fund travel and training for recruits drawn from vulnerable communities in East Africa. Countries like Somalia, Uganda, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Mozambique were highlighted as potential sourcing grounds, with ultimate destinations pointing to ISIS strongholds in Yemen. Such cross-border recruitment poses a dire threat to regional stability, as noted in recent United Nations reports on African extremism.

Mwita’s narrative paints a starkly different portrait. Speaking from his Mombasa residence, the lawyer, flanked by supporters including Law Society of Kenya officials, described the ordeal as a “witch hunt against independent counsel”.

He insisted the disputed transactions represented nothing more than legitimate legal fees earned from representing terror suspects in court. “Every Kenyan deserves a defence, no matter the charge,” Mwita stated emphatically, his voice steady despite the visible strain of 18 days in detention.

“These were payments for my services, documented and above board. To twist that into terror support is an assault on justice itself.” His legal team, led by figures like Martha Karua and Lempaa Soyinka, echoed this sentiment during earlier hearings, arguing that the Prevention of Terrorism Act should not criminalise advocacy work.

The courtroom drama unfolded at Kahawa Law Courts, where Principal Magistrate Gideon Kiage presided over the proceedings. On December 3, Mwita and two co-accused, Mariam Ali Abdalla and Stephen Kiveve Musembi, were formally charged under Sections 5(1) and 8(1) of the Act.

These provisions outlaw providing property or services for terrorist acts and handling assets controlled by designated groups. While Mwita walked free on personal bond after pleading not guilty, his co-defendants remain remanded, awaiting bail rulings later this month. The court scheduled his next mention for January 20, 2026, allowing time for disclosures and further evidence gathering.

This episode shows broader tensions in Kenya’s fight against terror financing through crypto channels. The ATPU’s operation netted 22 suspects, uncovering a network allegedly blending legitimate remittances with covert support for groups like Al-Shabaab affiliates.

Financial forensics experts emphasise the challenge: distinguishing clean transactions from dirty ones in a blockchain’s opaque ledger. Mwita’s case, in particular, highlights risks to lawyers who tread sensitive terrains. Over the past decade, he has championed rights for those accused in bombings and radicalisation plots, earning both acclaim and suspicion.

Public reaction has been polarised. Human rights advocates hail Mwita’s release as a win for due process, warning that overreach could chill legal practice. Conversely, security hawks decry it as leniency toward enablers, citing past links between coastal clerics and global jihadists.

As Kenya grapples with evolving threats, Mwita vows to clear his name fully. “I stand unbowed,” he concluded in his statement, “ready to fight not just for my freedom, but for the principle that no one is guilty until proven so.”

This saga may yet influence how courts navigate the intersection of digital finance, national security, and constitutional safeguards. For now, the Chacha Mwita crypto terror probe serves as a cautionary tale in an era where bytes can fund battles.